Metamorphosis of the future

Solo show by Maloles Antignac

Metamorphosis of the future

Solo show by Maloles Antignac

2 June - 1 July 2022

Credits

This is Jackalope

Juan de Sande

This Side Up

Bombykol

At the end of the 21st century, the city of Junygrat was divided into two large areas: the right side of the Pingda River housed a giant conglomeration of silkworm farms and the Hospital, made up of multiple skyscrapers, stood on the left flank in a monumental architectural ensemble. Most of the few remaining inhabited dwellings were on this same left flank, closer to the hills than to the riverbank.

S. woke up like every morning to the sound of machines downstairs. The window was open and through it entered a strong smell of wet earth intoxicating and addictive at the same time and that permeated the entire room. It hadn't stopped raining in weeks. She greatly enjoyed the rainy season, although each year it lasted less. She buried her face in the pillow, liking the feel of silk. Then she turned around and opened her eyes. For the first time in years, she was able to observe the furniture in her room, the shapes, the colors. She could perceive the textures through the signals that her retinas sent to the brain. She covered her face with the pillow again, this time enjoying the idea that the silk that caressed her face came from the same proteins that she had implanted in her eyes.

L. is S.'s daughter. She no longer lives in the city, like all young people her age. She emigrated to the countryside to learn how to farm and to try to get a small plot of land. Today she has come to Junygrat to visit her mother, but this visit and the long journey from the other side of the valley hid a parallel reason: after months of thinking about the matter, L. had decided to go to the city to pick up her first dose of Bombykol, the only one she would ever have access to.

The rulers of the early 22nd century decided to administer a single dose of Bombykol free of charge to each "human being" (for the oldest inhabitants this new terminology was still curious to refer to people, but after all, language advanced at the rate that society did or, rather, the ecosystem. The borders between what it is to be human or animal had already been blurred for years. We were becoming more and more hybrid beings).

The Government wanted to remove Bombykol from the danger it could cause being available in the black market and underground economies, so it decided to control its distribution. Its free circulation could have meant an excessive growth of the population or that it would be used as a recreational drug and, in addition to all that, there was the risk of being used as a weapon of war if it fell in the wrong hands. That is why it was decided to control and limit Bombykol distribution. For that same reason, L. and the other "human beings" could only try it once.

The rattle of the train always made L. sleepy, but today she was too restless to fall asleep. She was trying to distract herself by reading a book of poems by Fy Inkle, a young author who had been left out of the system after her addiction to Bombykol. Her books still managed to find their way into underground circles:

(Bombyx tangerine who dreams of

Bombyx mori who dreams of

Bombyx robot who dreams of

And back.

The queen of insects is now

The queen of humans is now

Bombykol queen

– Come on, it's your time)

She took a picture of the poem and sent it to R., the only person who knew she would take her dose of BK (short for Bombykol). She was nervous, but she had a plan. First, she would visit her mother, tell her the news about her decision to take her dose. Then, go to the BK Distribution Institute where she had an appointment, and finally go into the hills, as was the tradition.

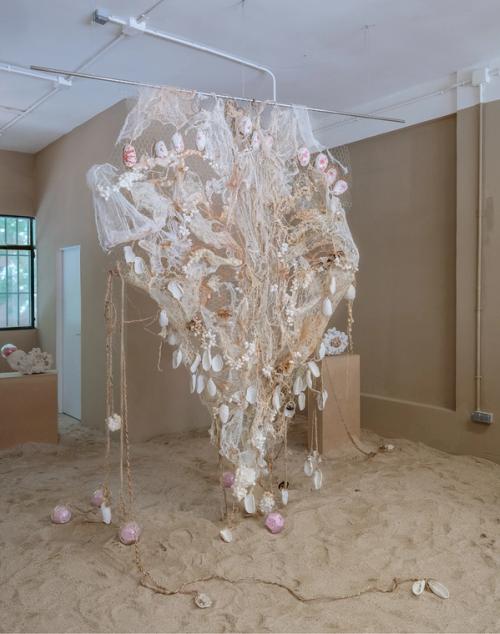

R. liked to stay up late. They were fascinated by wandering around the strange outskirts of the WyxWyx farm clusters, following those winding paths and dreamscapes that circled the compound on the right bank. After walking for about fifteen minutes, the lights were left behind. In the darkness, those strange shapes were beginning to appear, splashed on the uneven surface. Organic forms, a mixture of fire and earth, joined to geometric forms of silk polymer nanofibers, alternated with frayed cascades of silken cocoons, cobwebs indicating that we were close to the worm farms.

R. was one of the lucky humans who had received a skin implant, thanks to silk fibroin. It was prescribed as a treatment for burns and other conditions caused by the sun, which had increasingly become more terrifying and unbearable than in previous decades.

R. was the closest one to L. That night, they would meet her in the Junygrat hills to accompany her on her first and only dose. There, they had ingested their own dose two years ago. With it, they had achieved the transformation to double sex, reproducing successfully.

For years now, bringing a new human to life had gone from being a personal and private decision to a collective, thoughtful and governmental issue, forced by the urgency of ending the problem of human overpopulation in a wounded planet. New communities began to take shape from the creation of hybrid beings arising from imagined kinship and thought for extreme environmental conditions. New worldviews with previously defined characteristics were underway. L. and R. were part of a new genesis: the first generation resulting from the crossover between two species, "human beings" and silk butterflies.

Egg, larva, chrysalis and butterfly

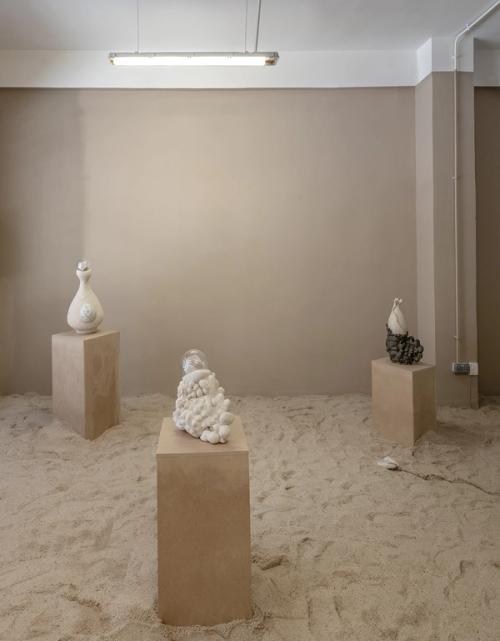

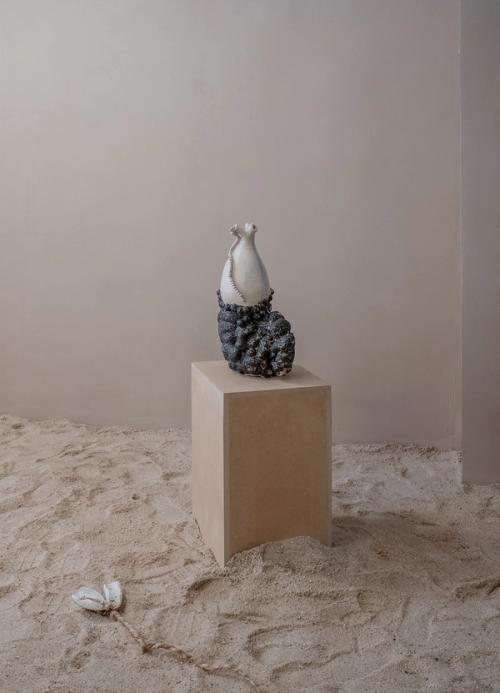

Maloles Antignac's work outlines a science fiction scenario from a sculptural and installation perspective. Through an intuitive process, the artist creates objects from glazed and unglazed stoneware, copper, PLA polymer nanofibers, silk polymer nanofibers, and glass with mutating forms in a suspended state. In a paused, frozen evolution. Fossils of an imagined future time, where the understanding of the material world intertwines the natural, the technological and the organic without distinction as parts of the same cycle. Antignac reflects on many of the concerns that we have nowadays, driven by the need to reconfigure our relationships with a damaged planet Earth and with all its inhabitants: humans, animals, plants, inanimate objects and technologies. The exhibited pieces take us into a kind of surrealist post-natural landscape from which to speculate about possible futures.

At the end of the 21st century, the city of Junygrat was divided into two large areas: the right side of the Pingda River housed a giant conglomeration of silkworm farms and the Hospital, made up of multiple skyscrapers, stood on the left flank in a monumental architectural ensemble. Most of the few remaining inhabited dwellings were on this same left flank, closer to the hills than to the riverbank.

S. woke up like every morning to the sound of machines downstairs. The window was open and through it entered a strong smell of wet earth intoxicating and addictive at the same time and that permeated the entire room. It hadn't stopped raining in weeks. She greatly enjoyed the rainy season, although each year it lasted less. She buried her face in the pillow, liking the feel of silk. Then she turned around and opened her eyes. For the first time in years, she was able to observe the furniture in her room, the shapes, the colors. She could perceive the textures through the signals that her retinas sent to the brain. She covered her face with the pillow again, this time enjoying the idea that the silk that caressed her face came from the same proteins that she had implanted in her eyes.

L. is S.'s daughter. She no longer lives in the city, like all young people her age. She emigrated to the countryside to learn how to farm and to try to get a small plot of land. Today she has come to Junygrat to visit her mother, but this visit and the long journey from the other side of the valley hid a parallel reason: after months of thinking about the matter, L. had decided to go to the city to pick up her first dose of Bombykol, the only one she would ever have access to.

The rulers of the early 22nd century decided to administer a single dose of Bombykol free of charge to each "human being" (for the oldest inhabitants this new terminology was still curious to refer to people, but after all, language advanced at the rate that society did or, rather, the ecosystem. The borders between what it is to be human or animal had already been blurred for years. We were becoming more and more hybrid beings).

The Government wanted to remove Bombykol from the danger it could cause being available in the black market and underground economies, so it decided to control its distribution. Its free circulation could have meant an excessive growth of the population or that it would be used as a recreational drug and, in addition to all that, there was the risk of being used as a weapon of war if it fell in the wrong hands. That is why it was decided to control and limit Bombykol distribution. For that same reason, L. and the other "human beings" could only try it once.

The rattle of the train always made L. sleepy, but today she was too restless to fall asleep. She was trying to distract herself by reading a book of poems by Fy Inkle, a young author who had been left out of the system after her addiction to Bombykol. Her books still managed to find their way into underground circles:

(Bombyx tangerine who dreams of

Bombyx mori who dreams of

Bombyx robot who dreams of

And back.

The queen of insects is now

The queen of humans is now

Bombykol queen

– Come on, it's your time)

She took a picture of the poem and sent it to R., the only person who knew she would take her dose of BK (short for Bombykol). She was nervous, but she had a plan. First, she would visit her mother, tell her the news about her decision to take her dose. Then, go to the BK Distribution Institute where she had an appointment, and finally go into the hills, as was the tradition.

R. liked to stay up late. They were fascinated by wandering around the strange outskirts of the WyxWyx farm clusters, following those winding paths and dreamscapes that circled the compound on the right bank. After walking for about fifteen minutes, the lights were left behind. In the darkness, those strange shapes were beginning to appear, splashed on the uneven surface. Organic forms, a mixture of fire and earth, joined to geometric forms of silk polymer nanofibers, alternated with frayed cascades of silken cocoons, cobwebs indicating that we were close to the worm farms.

R. was one of the lucky humans who had received a skin implant, thanks to silk fibroin. It was prescribed as a treatment for burns and other conditions caused by the sun, which had increasingly become more terrifying and unbearable than in previous decades.

R. was the closest one to L. That night, they would meet her in the Junygrat hills to accompany her on her first and only dose. There, they had ingested their own dose two years ago. With it, they had achieved the transformation to double sex, reproducing successfully.

For years now, bringing a new human to life had gone from being a personal and private decision to a collective, thoughtful and governmental issue, forced by the urgency of ending the problem of human overpopulation in a wounded planet. New communities began to take shape from the creation of hybrid beings arising from imagined kinship and thought for extreme environmental conditions. New worldviews with previously defined characteristics were underway. L. and R. were part of a new genesis: the first generation resulting from the crossover between two species, "human beings" and silk butterflies.

Egg, larva, chrysalis and butterfly

Maloles Antignac's work outlines a science fiction scenario from a sculptural and installation perspective. Through an intuitive process, the artist creates objects from glazed and unglazed stoneware, copper, PLA polymer nanofibers, silk polymer nanofibers, and glass with mutating forms in a suspended state. In a paused, frozen evolution. Fossils of an imagined future time, where the understanding of the material world intertwines the natural, the technological and the organic without distinction as parts of the same cycle. Antignac reflects on many of the concerns that we have nowadays, driven by the need to reconfigure our relationships with a damaged planet Earth and with all its inhabitants: humans, animals, plants, inanimate objects and technologies. The exhibited pieces take us into a kind of surrealist post-natural landscape from which to speculate about possible futures.